Compassion isn’t always soft and gentle; sometimes it means being forceful and fierce.

In the recent Senate confirmation hearings for the U.S. Supreme Court, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford stood up to tell the world about her memories of the humiliating and sexually aggressive way that she said Judge Brett Kavanaugh violated her as a teenager.

Her act took incredible bravery. What really struck me, however, was the demeanor of Dr. Blasey Ford herself. While she spoke with confidence when discussing her area of expertise—the psychology of trauma—at other times she spoke like a young girl who needed to placate all the powerful men around her so they would like her. This doesn’t undercut the courage she showed for being there—it was tremendous—but she clearly felt she had to be soft and sweet to be heard.

And she was probably right. If she had shown her righteous indignation at Kavanaugh for derailing her life, she probably would have been discredited. While Kavanaugh’s anger at being “wrongly” accused was celebrated by many male senators and arguably led to his confirmation, Ford was allowed to show her pain at being victimized, but no more than that.

The fact is that women are not allowed to show anger in order to stand up for themselves. When women encounter pain and suffering—in others and in ourselves—we are expected to respond with gentleness, tenderness, and warmth. But today, we need a different response: fierce self-compassion.

Compassion is aimed at alleviating suffering and can be ferocious as well as tender, “yin” as well as “yang”—the mother gently comforting her crying child or the mother bear fiercely protecting her cubs. Feminine ideals need to include anger and resolve if we want to successfully care for ourselves and each other, move beyond male dominance, and make a difference in the issues facing our world today.

The yin and yang of self-compassion

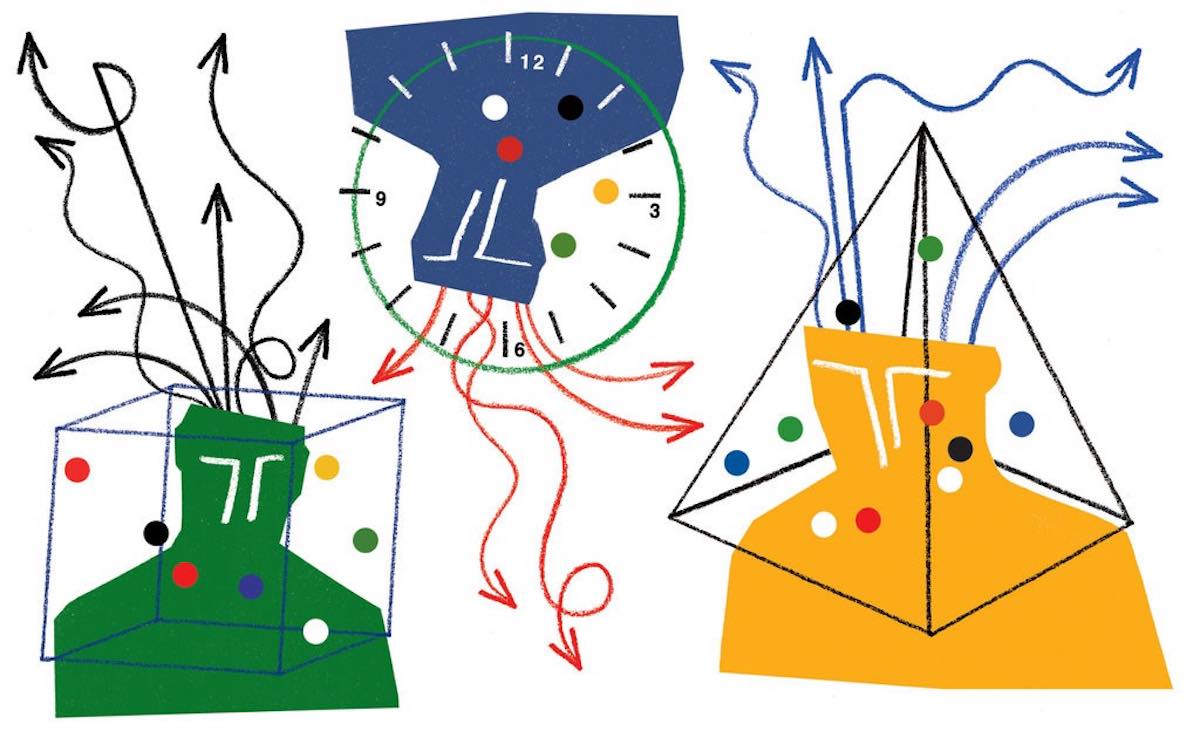

According to my work, the three core components of self-compassion are self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness of suffering. These manifest in “yin” self-compassion as loving, connected presence. Self-kindness means we tenderly care for ourselves when in pain. Common humanity involves recognizing that suffering is part of the shared human condition. Mindfulness allows us to be with and validate our pain in an open, accepting manner. When we hold our pain in this way, we start to transform and heal.

When most people think of self-compassion, they imagine the yin version. But self-compassion also has a “yang” form. With yang self-compassion, the three components show up as fierce, empowered truth. Self-kindness means we fiercely protect ourselves. We stand up and say, “NO! You cannot harm me in this way.” Common humanity helps us to recognize that we are not alone; we don’t need to hang our heads in shame. We can stand together with our brothers and sisters in the experience of being harmed and become empowered as a result. Me too! And mindfulness manifests as clearly seeing the truth. We no longer choose to avoid seeing or telling in order to not rock the boat. The boat needs to be rocked.

When we hold our pain with fierce, empowered truth, we can speak up and tell our stories, to protect ourselves and others from being harmed.

In yin self-compassion, we hold ourselves with love—validating, soothing, and comforting our pain so that we can “be” with it without being consumed by it. In yang self-compassion, we act in the world in order to protect ourselves, provide what we need, and motivate change to reach our full potential.

Research indicates that both aspects of self-compassion lead to well-being. Self-compassion allows us to “be” with ourselves tenderly (yin) but also to take action (yang), so that we can support ourselves and thrive. For instance, yin self-compassion reduces depression and anxiety by replacing self-judgment with self-acceptance. When we soothe and comfort ourselves in the midst of difficult emotions, we no longer get lost in the rabbit hole of shame and inadequacy, but take refuge in the safety of our own warmth and care. We become happier and more satisfied with our lives as a result.

At the same time, yang self-compassion allows us to actively cope with life challenges. Whether it’s combat, divorce, cancer, or parenting a special-needs child, self-compassion provides us with the resilience needed to stand strong without becoming overwhelmed. Yang self-compassion motivates us to keep going even after failure and setbacks, providing grit and perseverance in the face of adversity.

Balancing tenderness and fierceness

Traditional gender roles allow women to be yin, but if a woman is too yang—if she gets angry or fierce—people often get scared and call her names (the b-word comes to mind). Men are allowed to be yang, but if a man shows too much vulnerability, he risks being kicked out of the boys’ club of power. In many ways, the #MeToo movement can be seen as the collective arising of female yang. We are finally speaking up to protect ourselves, our sisters, our daughters, and our sons.

If we are yin without yang, we will continue to be silenced, to be abused, to be disregarded and disempowered. If we are yang without yin, however, we are at risk of becoming self-righteous, of forgetting the humanity of others, of demonizing men. Like a tree with a solid trunk and flexible branches, we can stand strong while still embracing others as part of an interdependent whole. We need love in our hearts so we don’t perpetuate a cycle of hate, but we need fierceness so that we don’t let things continue on their current harmful path.

It is challenging to hold loving, connected presence together with fierce, empowered truth because their energies feel so different, but we need to do so if we are going to effectively stand up to patriarchy, racism, and the people in power who are destroying our planet. We need both simultaneously, as advocated by great leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, Mother Theresa, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

How do we do this? I’m just figuring it out for myself. In the past, I’ve tended to be yin in some moments and yang in others, but I have found integration difficult. My self-compassion practice helps me to not care what other people think of me, because I can provide myself with the validation and support I need. But when my yang is in full force, sometimes I don’t think enough about other people and the effects of my behavior on them. I’m working hard to honor and integrate both energies.

I find it’s helpful to recognize which is being activated in the moment, then take the time to make sure the other energy is also present. When I’m being tender toward myself or others in a yin way, for instance, I consciously ask whether the force of yang is needed. And when I feel yang energy arising, it try to make sure that I have enough yin, to remind myself that the use of force is more effective when it is combined with tenderness. I make a lot of mistakes and often don’t get it right, but I know that this is the only way forward.

I hope that soon women such as Dr. Blasey Ford are allowed to be fully empowered, to temper their sweetness with steel. I hope that we are all able to call upon the tenderness and fierceness that is our birthright. If we are going to have any chance of achieving equality, women will have to wake up, say no, and give up on receiving the approval of men. We will need to embody fierce, empowered truth. Many won’t like it, but that’s okay. We can heal our wounds with the salve of loving, connected presence, giving ourselves what we need.

While it is crucial that we take action to change the political system, the first place to start is with ourselves. The next time we are at the grocery store with a rude checkout person, or in a conflict at work, or confronted with a difficult life challenge, we need to turn inward and call up both yin and yang self-compassion in a balanced manner. We need to learn to use caring force to change ourselves and our world. The time is now.

By Kristin Neff